Pneumatic Cylinder Guide for Beginners | Working & Types

They Move Everything — A Beginner’s Guide to Pneumatic Cylinders That Do All the Work!

The Power Behind Industrial Movement

Step one foot onto a modern automated factory floor and one machine quickly becomes the star: the humble, hardworking cylinder. They’re absolutely everywhere. Clamping this piece, shoving that item down the line, holding something tight for a weld. If it’s fast and straight-line, chances are a pneumatic cylinder is driving it.

The entire principle of reliable industrial automation rests on these precise, powerful, and ridiculously common movements. No matter how clever the electronics or robotics get, at some point, you still need reliable physical force, right?

That force is delivered, quietly, efficiently, and cleanly, by the system of air-powered workhorses we’re talking about here.

For anyone who’s ever had to spec a new assembly jig or simply diagnose a slow packaging machine, you quickly learn you have to know these cylinders cold. In this guide, we’re going through all of it. We’ll break down the very simple pneumatic cylinder working principle, clear up confusion on component selection, and share some real-world secrets on why air quality affects cylinder life. No more guessing games!

What Is a Pneumatic Cylinder?

Simply put, it’s the motor for straight-line pushing and pulling. A pneumatic cylinder is the machine element that grabs air pressure from the compressor—that costly utility you run all day—and turns it into clean, controllable physical movement.

Forget formal descriptions. Think of it like this: A heavy, rugged steel tube (the cylinder) is completely sealed off. Inside is a strong piston connected to an external rod. You shove high-pressure air into one end, and it instantly forces the rod out the other end. That’s it. It’s an air-powered actuator.

In a catalogue, you’ll see the official title of a linear motion actuator, because that rod doesn’t spin; it goes back and forth. You won’t use these for driving conveyors—you’ll use them for things like operating machine safety gates or punching small holes. Any job that requires a single, powerful push or pull stroke is best handled by this kind of pneumatic actuator. They are rugged simplicity.

How Pneumatic Cylinders Work

The elegant thing about the pneumatic cylinder working principle is that it is a pure demonstration of pressure: when force has nowhere to go but one direction, it goes that direction with all its power.

Role of Compressed Air

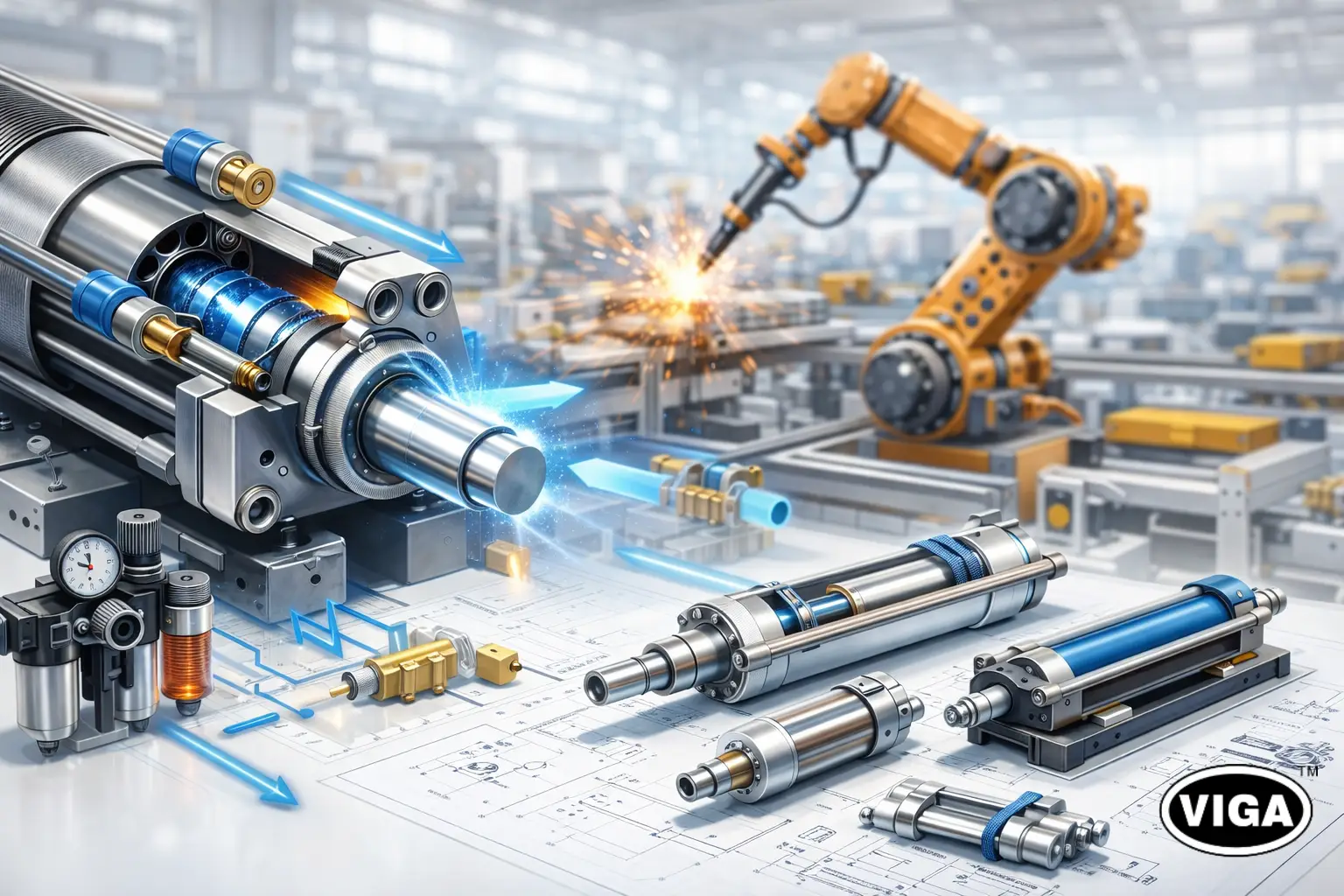

The air comes from your facility’s system, but its path is strictly controlled by valves. That valve directs the high-pressure compressed air actuator energy toward the cylinder’s chambers, effectively deciding where the muscle power is needed at that moment. The moment that high-pressure source is hooked up, the system is primed.

Piston and Cylinder Movement

The sealed, interior piston is what actually gets the job done inside the casing. It’s sitting in there, essentially separating the volume of the tube into a ‘forward’ side and a ‘back’ side. You want to make the rod go out? You create more pressure on the back side.

Conversion of Air Pressure into Linear Force

- Your directional valve clicks, opening the flow and dumping air at high pressure into the chamber behind the piston head.

- At the same instant, the front chamber air needs a fast path out—that air is instantly released through a silencer.

- Since the force against the back of the piston is massive and the force against the front of the piston has gone to zero, the pressure differential creates a swift, continuous linear force until the rod hits the end stop.

It’s all about creating and managing a massive imbalance. Fast and dependable every time.

Main Components of a Pneumatic Cylinder

If you’re expected to maintain these, you need to know which parts are disposable and which parts are critical structure. When checking component specifications, pay close attention to the structural aspects.

- Cylinder Barrel: It’s the fixed body of the tool. Key design point: the inner surface must be flawless, with zero nicks or rust spots, or your seals won’t last ten minutes.

- Piston and Piston Rod: The piston is the round head that air pushes. The piston rod is the thick, hardened steel bar that actually extends out into the machinery. A bent rod is an almost instantaneous trip to the scrapyard.

- End Caps (Heads): These are the structural lids that seal the unit shut and provide the necessary Air Ports to feed pressure. They often contain the mounting threads and shock absorbers.

- Seals and Bearings: These two wear parts define the entire lifespan. The Seals are elastomeric rings that contain the pressure, and the Rod Bearings are the bronze collars that ensure the rod stays straight. Failures in this area mean immediate loss of power.

Types of Pneumatic Cylinders Explained Simply

Which type you use boils down to how complex the application is—can you use simple return action, or do you need control for both movements?

Single-Acting Pneumatic Cylinders

This cylinder has only one power stroke: the push (or the pull). It only uses one air line. When you stop supplying air, a pre-installed return spring takes over, shoving the piston back to the home position.

- Key trade-off: It saves on air consumption, but the piston has to work against that internal spring force, meaning its overall pushing strength is significantly less than the double-acting unit. Simple for tasks like quick door openings.

Double-Acting Pneumatic Cylinders

This is the machine’s choice for precision control. A double-acting pneumatic cylinder has power on both ends: air to push out, and separate air line control to pull it back in.

- Key advantage: Provides maximum force for the cylinder’s size in both directions. Essential for pneumatic motion control applications that require high force throughout the entire stroke length. It does, however, use twice the volume of compressed air.

Rodless Pneumatic Cylinders

Imagine trying to stabilize a long piston rod when moving a 400-pound load over a 15-foot distance. Impossible. The rodless pneumatic cylinders solved this problem by sealing the air in the barrel but letting an external sliding saddle do the heavy movement along a guide. They save tremendous space and are vital in large gantry and positioning systems.

Where Pneumatic Cylinders Are Used

These units are the quintessential industrial automation components because their usage is so widespread and reliable.

- Manufacturing and Assembly Lines: Their high cycle speed is required to clamp objects for assembly and to provide necessary quick pushes during high-speed material handling systems.

- Packaging Machines: In food and medical processing, air-powered actuators are the absolute standard. No possibility of hydraulic oil leaks into sterile packaging means they are non-negotiable for pushing items, sealing bags, or controlling filling spouts.

- Automotive Production: Anywhere a part has to be accurately held during the joining process—be it clamping for a robotic weld or accurately positioning panels—a large-bore industrial pneumatic cylinders does the work.

- Textile and Paper Industries: Controlling cutting blades, activating folding arms, or quickly indexing large sheets into a final printing stage.

Why Pneumatic Cylinders Are Preferred in Industry

The consistent industry love for this technology boils down to the fact that they have simplified and optimized performance in ways that are hard for other systems to beat.

- Fast Response Time: No motor ramp-up or heavy oil inertia. When the valve flips, the cylinder fires, allowing for exceptional machine speed in assembly operations.

- Clean and Safe Operation: The operational medium—air—is entirely non-contaminating and inherently safe. The fact that an air leak causes no environmental hazard is huge for workplace safety and compliance.

- Cost-Effectiveness: They’re cheap to purchase, last a long time, and the “fuel” is just compressed air, a highly centralized and economical utility to operate per cycle count.

- High Reliability: Due to few moving pneumatic cylinder components and an uncomplicated mechanical design, they handle severe heat, dirt, and repetitive stress much better than complex servo systems.

- Easy Maintenance: Common problems in pneumatic cylinders (seals, air quality) are typically easy to fix, focusing on inexpensive consumables, rather than multi-axis repairs.

Pneumatic Cylinders vs Hydraulic Cylinders

If you don’t do this analysis up front, you risk misapplying technology, which gets very expensive. This is about application, not capability.

- Pressure and Force Comparison: Pneumatics is your low-power, fast solution, limited to pressures the tank holds (usually 7-8 bar). Hydraulics is for pure brute force—a ram press pushing steel or excavators. That high-power force comes from oil systems operating well over 200 bar.

- Speed and Control Differences: If you need lightning speed (e.g., 60+ cycles/min), use pneumatics. Hydraulic power is slower but holds positions rigidly because the oil does not compress—essential for high-tonnage locking.

- Maintenance and Safety Aspects: Any leak on a hydraulic system is a containment disaster, fire risk, and slip hazard. With pneumatics, it’s just air—a negligible risk. The simple pneumatic cylinder maintenance of FRLs is preferred to constant oil monitoring.

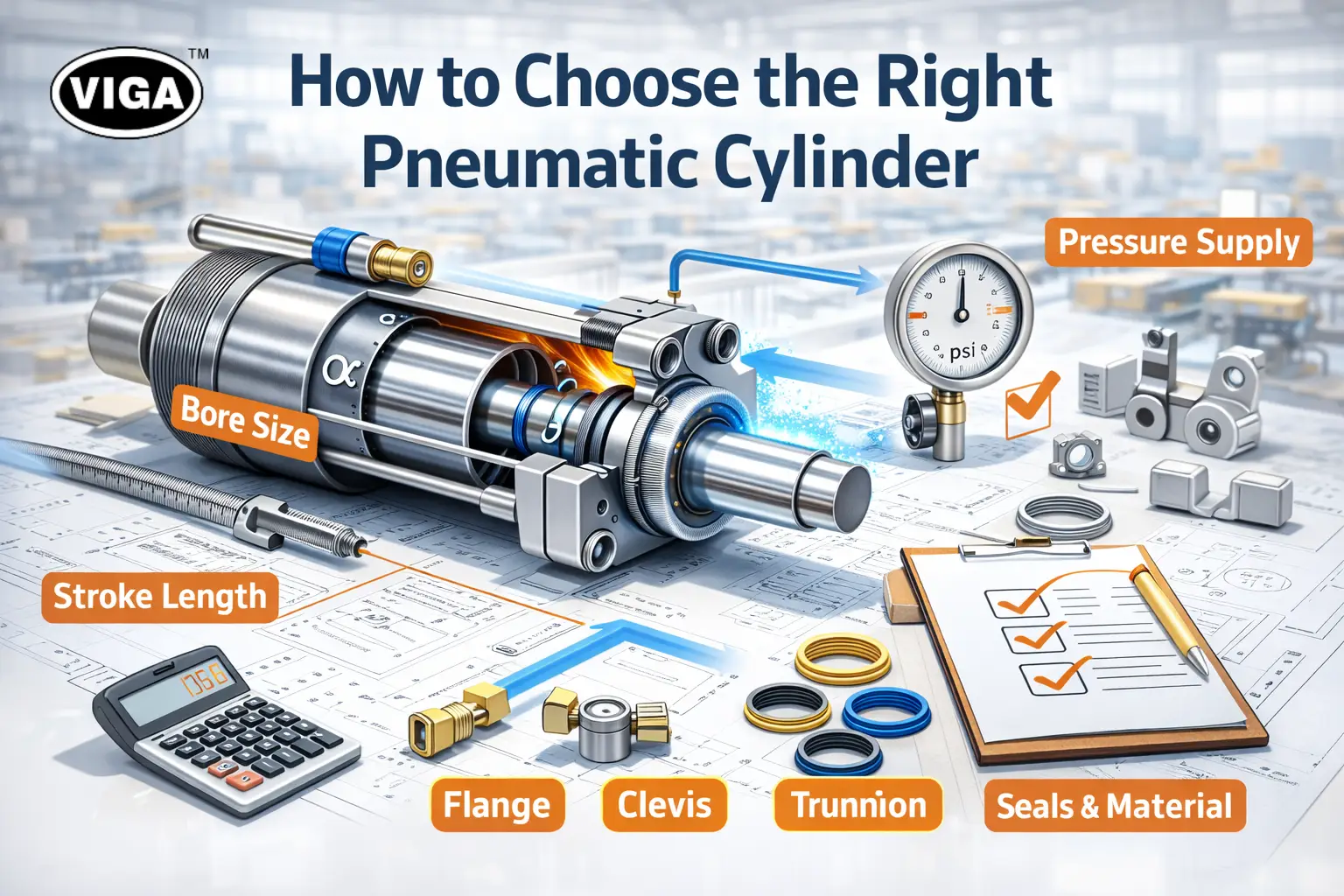

How to Choose the Right Pneumatic Cylinder

If you undersize it, the cylinder struggles, heats up, and quickly destroys itself. Oversize it, and you’ve simply wasted money. Use the formula.

- Define the Required Stroke Length: This part is simple—how far must the component move? Pick the standard size that gives you a little extra wiggle room on the ends. No surprises here.

- Bore Size and Force Calculation: This is the most critical step and requires calculation. Take your known operating pressure (P) and calculate the necessary piston area ( A=F/P ) that can support your maximum necessary force ( F ) at an 80% safety margin. If you don’t do this force and stroke calculation, you will fail. The Bore Size follows directly.

- Confirm Pressure Supply: Ensure that the smallest required working pressure will actually be consistently available on your floor—air line pressure often fluctuates based on system demand.

- Analyze Mounting Options: Will the cylinder push dead-straight (Flange Mount)? Or will it have to pivot slightly while working (Clevis or Trunnion Mount)? Incorrect mounting immediately puts dangerous side loads on the rod.

- Environmental Assessment: Select proper seals (like Teflon or Viton) and barrel materials (Stainless Steel) that are compatible with any nearby corrosive agents, dust, or temperature extremes. Don’t be cheap on seals!

Common Problems and Failures in Pneumatic Cylinders

The biggest piece of advice: most of your failures start upstream in your air supply. It’s almost never the cylinder’s fault!

- Air Leakage (Hissing Noise): An annoying and costly symptom. While external connection points are common culprits, failure of the piston’s internal seals allows high-pressure air to bleed straight past the piston, which equals wasted energy and almost no force output.

- Seal Degradation/Wear: Seals are destroyed by contamination. Dirty air containing moisture, fine rust particulate, or grit will score the smooth piston surface and shred the elastomer seal materials faster than anything else. This also leads to rod bending or ‘whipping.’

- Misalignment: This issue, created during initial installation or setup, generates enormous friction that heats up the internal components. High heat cooks the internal plastic and rubber, and seals go bad fast. This will require new seals, new bearings, and usually a completely new rod.

- Sluggish Action: This is when the cylinder pushes, but it’s slow. This isn’t a leak problem, but a restriction. Usually, a heavily clogged air muffler on the exhaust port (or regulator set too low) isn’t letting the pressure vent fast enough.

Maintenance Tips to Extend Pneumatic Cylinder Life

The majority of your time and effort needs to go into the component that delivers the air—not the cylinder itself. Your pneumatic cylinder maintenance routine must be heavily protective.

- Prioritize Air Quality (FRL Unit Health): The non-negotiable step. Your FRL (Filter, Regulator, Lubricator) is your first line of defense. Filters must be swapped often to ensure no debris gets to the piston. Check for and drain condensation from the bottom of the air line tanks religiously.

- External Rod and Seal Inspection: Always check the piston rod for fine scratches (indicating external grit damage) and visible seepage (the hallmark of a rod seal failure). Small external failures need to be addressed before they lead to catastrophic internal pressure loss.

- Alignment Must Be Perfect: Check that mounting bolts are snug but not over-tightened to prevent structural binding. Manually check for any lateral stress on the piston rod during the first few dozen cycles of operation. Address side loads immediately.

- Establish a Cycle-Count-Based Schedule: Seals and components are only rated for so many million cycles. Keep maintenance records based on actual usage time, not just the date, to predict failures and prevent an emergency shutdown.

Comparison Table: Pneumatic Cylinders in Action

This should put the whole picture into context—why we pay money for a power utility versus relying on labor alone.

Parameter | Automated Action (Pneumatic Cylinder) | Pure Human Labor |

Movement Control | Electronic precision. Consistent and 100% Repeatable. | Varies by the individual. Inconsistent and easily fatigued. |

Speed/Rate | Very Fast Cycling. Optimal for High-Volume Production. | Slow. Limited to single tasks and low repetition rate. |

Efficiency | Excellent: Low running costs vs. high speed output. | Poor: High and constant cost of labor for low volume tasking. |

Maintenance | Highly Predictable; Mostly air system management. | Unpredictable; Susceptible to accident, injury, or lack of skill. |

Conclusion: The Silent Workforce of Automation

It’s clear that the cylinder is far more than just a tube. It’s the dependable, precise, and most often, overlooked piece of machinery that guarantees movement across the facility.

You are now equipped with the knowledge needed. From understanding the force ratios involved in single acting vs double acting pneumatic cylinder sizing to applying a real-world pneumatic cylinder maintenance strategy focused on clean air, you’re ahead of the curve. These reliable little actuators solve countless problems cheaply and cleanly.

Your key takeaway should be: Don’t guess the bore size. Don’t compromise on air filtration. Respect those rules, and the cylinder you install today will be quietly pushing things tomorrow—a dedicated piece of your automation for years to come.

FAQs

Q1: What is a pneumatic cylinder used for?

A pneumatic cylinder is primarily used to apply a straight-line mechanical force for functions like lifting, positioning, and fast-paced clamping. They are the go-to power element for providing muscle in virtually all industrial, rapid-cycle automation systems.

Q2: How much force can a pneumatic cylinder generate?

The output force is directly proportional to the available air pressure and the cylinder’s piston diameter. They are capable of moderate forces—sufficient for light and medium loads. The maximum, safe force calculation should always be done during the design phase to avoid component overload.

Q3: What is the difference between single and double acting cylinders?

A single-acting cylinder only uses air to move the rod one way, relying on an internal spring for the return stroke. A double-acting cylinder uses a dedicated air line to power both the extend and retract strokes, giving you control over the action in both directions.

Q4: How long do pneumatic cylinders last?

A well-maintained cylinder can achieve service life into the millions of cycles. Longevity is entirely dependent on keeping the air supply filtered and dry; contaminants in the air cause seals to fail prematurely, which immediately drops the effective service life.

Q5: Are pneumatic cylinders better than hydraulic cylinders?

It depends entirely on the task! Pneumatics are much better for high speed, low-to-medium force, and cleanliness requirements. Hydraulics are only superior when an extreme amount of force (e.g., thousands of pounds of pressure) is needed, accepting slower speed and fluid maintenance risks as a necessary tradeoff.